Laboratory animal numbers 2024

April 24th is World Day for Laboratory Animals. We are taking this day as an opportunity to publish the numbers of laboratory animals used by the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. Here you will find the number of animals per species and the stress levels of the experiments compared to previous years. In 2024, the majority of animal experiments at the Institute were carried out on mice and zebrafish for research into the infectious diseases malaria and tuberculosis. Experiments have also been carried out on rats and on the fish species Danionella cerebrum.

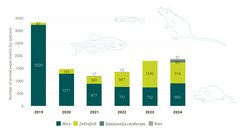

In 2024, 1875 animals were used for scientific purposes at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. The number of laboratory animals remains almost constant compared to the previous year (1774 animals). The majority of the animals used were mice (900 animals) and zebrafish (918 animals). As in 2021 and 2022, rats were also used for experiments in 2024 (57 animals). For the first time, experiments were carried out with the fish species Danionella cerebrum in 2024 (85 animals). Like zebrafish, these small fish are used in tuberculosis research. You can find a brief portrait on our experimental animals page.

Tuberculosis research with zebrafish and Danionella cerebrum

Every year, more than ten million people fall ill with tuberculosis and more than one million die of the disease. At the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, we are trying to understand the basics of tuberculosis infection: Mark Cronan's research group is investigating so-called tuberculosis granulomas—nodular clusters of immune cells that form around tuberculosis bacteria.

Granulomas prevent immune cells and antibiotics from reaching the tuberculosis bacteria. This makes the disease more difficult to treat and more difficult for the immune system to fight. Mark Cronan's research group is looking for ways to dissolve granulomas and make the bacteria accessible to antibiotics. Due to the complex interaction between pathogens and immune cells, granulomas can only be studied in living organisms.

Overview of laboratory animal numbers

A suitable model for tuberculosis granulomas

In humans, granulomas usually form in the lungs. Although they have gills instead of lungs, zebrafish are suitable model organisms for tuberculosis research—when infected with tuberculosis, they form structures that are very similar to human granulomas. Although mice are more common laboratory animals, they do not develop comparable granulomas. For these reasons, zebrafish are often used in tuberculosis research. The same applies to the fish species Danionella cerebrum, which is closely related to the zebrafish.

Animal experiments in tuberculosis research

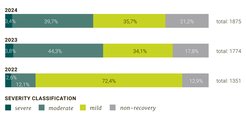

In order to study tuberculosis granulomas, the members of the research group infect zebrafish and Danionella cerebrum with the bacterium Mycobacterium marinum, a close relative of the human tuberculosis pathogen. The fish fall ill with the pathogen and form granulomas, which is why the experiment is classified as a medium contamination in the legal classification. The researchers are also breeding genetically modified fish to stain cells of the immune system, for example. The breeding is considered an animal experiment and is classified as low-stress. Further information on the severity levels of animal experiments can be found here.

Number of mouse experiments increased

Compared to 2023, the number of mice used increased in 2024 from 732 to 900. As in previous years, the animals were used for research into immune cells and the infectious disease malaria. In addition, the research group Regulation of the Innate Immune System conducted breeding experiments to investigate autoimmune diseases.

Genotyping was carried out on a large number of mice. The researchers use these experiments to check the genetic material of the mice to determine whether a genetic modification was successful. A small piece of tissue, usually taken from the ear, is all that is needed to obtain genetic material for the study. The tests are classified as low-stress experiments.

Animal testing according to stress levels

Animal experiments in malaria research

Almost 250 million people fall ill with malaria every year. The two malaria vaccines approved in recent years are a major step forward in the fight against the disease, but they still have to be administered several times in infancy and are less than 70 percent effective. Researchers are therefore continuing to search for vaccines.

In the Vector Biology research group, mice were used to test a potential vaccine against malaria. In order to identify the vaccine candidate, the experiments were preceded by extensive tests in cell cultures, which saved a large number of animal experiments. However, whether a vaccine provides the desired protection must be tested on living organisms.

Use of rats in research

In 2024, 57 rats were killed in the research group Cellular Microbiology for tissue removal. This was a continuation of the experiments carried out in 2021 and 2022. The experiments were used to research a cell type of the innate immune system, the so-called neutrophil granulocyte, which make up the majority of white blood cells and play an important role in immune defense.

Animal experiments remain an important part of infection research

Animal experiments are still indispensable in biomedical research—also at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. According to the current state of research, they are an important part of the range of experimental methods, especially for research into the complex mechanisms of our immune system

The research groups at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology use a variety of animal-free methods. These include, for example, computer models and experiments with cell cultures, bacteria, invertebrates and human donor tissue. Before researchers resort to animal experiments, it is always checked whether an animal-free method is sufficient to answer the scientific question.

Even if the development of alternative methods is constantly progressing and some animal experiments can now be replaced and the number of animals used can be reduced, a complete replacement of animal experiments is currently not foreseeable. These experiments will continue to be needed in the future to gain knowledge and develop new therapeutic approaches and methods.