History of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology

The Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology was founded in 1992, making it one of the first Max Planck Institutes in the former GDR. In 1993, the Max Planck Society (MPG) appointed Stefan H. E. Kaufmann as founding director of the Institute, followed by Thomas F. Meyer in 1994. After several years in temporary laboratory rooms in Monbijoustraße, the Institute moved to the new building on the Campus Mitte of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in 2000. At this time, the third director of the Institute, Arturo Zychlinsky, was appointed. In addition, research groups were established over the years, such as Elena Levashina's group, which still exists today. In the wake of the retirement of Directors Kaufmann and Meyer in 2019 and 2020, the MPG appointed eight new research groups. This diversity has shaped the Institute's profile to this day.

A new Institute

On March 13, 1992, the Senate of the Max Planck Society (MPG) decided to establish the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. The research focus of the Institute would be on host-pathogen interactions, including infectious diseases caused by bacteria, fungi and other single-celled organisms. Already at the time of the foundation, the MPG aimed for close networking with clinics and research departments at universities. This was a key factor in the choice of location: the campus of the long-established Charité University Hospital, which is located on the territory of the former GDR in the center of Berlin.

A location with history

The history of the Charité is closely linked to the research and treatment of infectious diseases. Faced with a spreading plague epidemic, it was founded in 1710 as a quarantine station and military hospital—at that time still far from the gates of Berlin. In the 19th century, the Charité was affiliated with the Humboldt University. This marked the beginning of an important era of medical research. Physicians such as Rudolf Virchow and Robert Koch used new approaches to link medical and scientific issues. Their work led to groundbreaking results in infection research: many pathogens were described for the first time, for example tuberculosis, which was rampant in Europe at the time, and researchers developed new treatment options and hygiene measures. The Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology would be built in this historic setting almost a hundred years later.

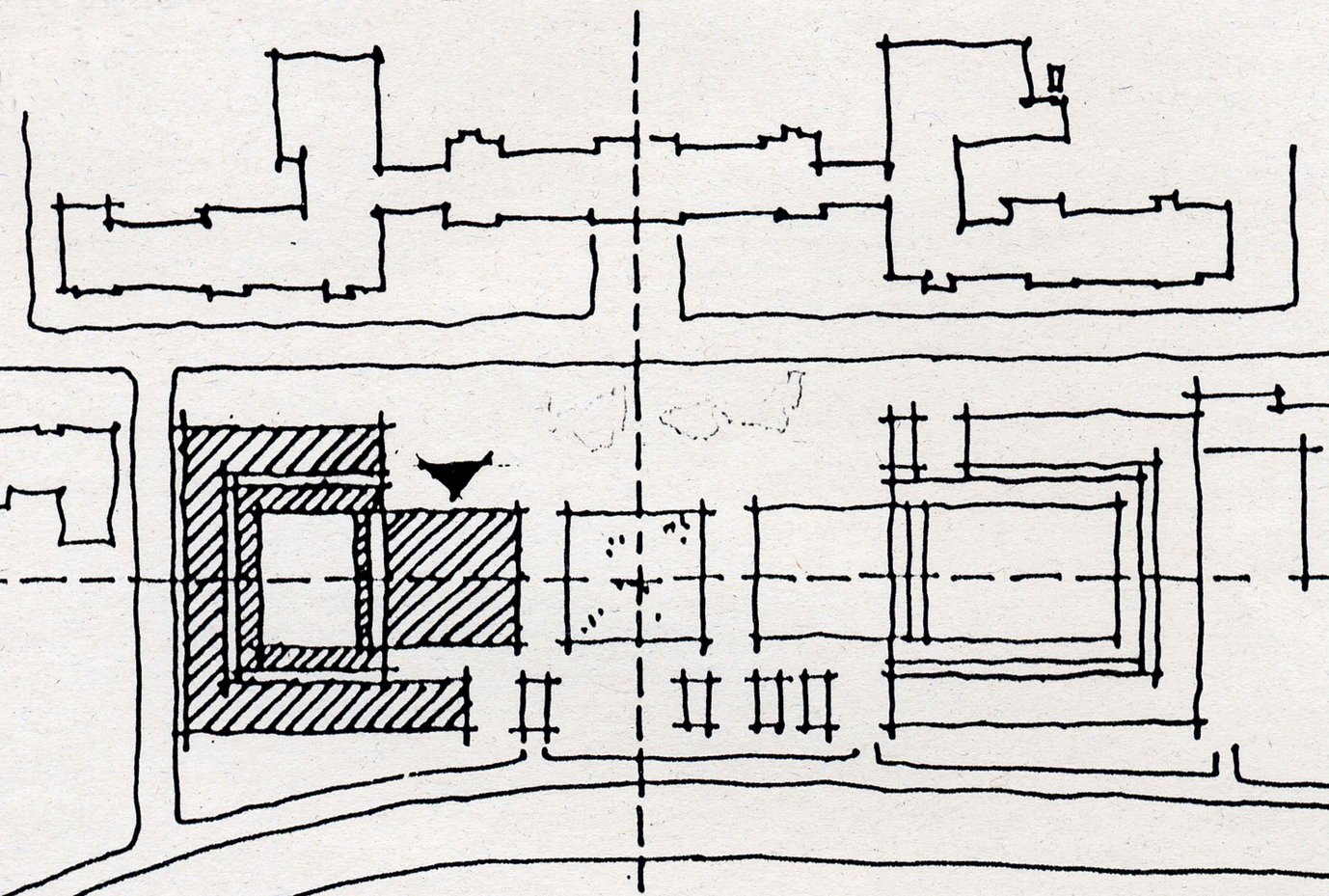

Obstacles to construction

The location on the historic campus placed high demands on the architects. For example, the tight confines of the site forced the individual departments within the building to be condensed. The building ground was also problematic due to its proximity to the Spree River and the soft sandy soil of Berlin's glacial valley, requiring a complex substructure with concrete columns up to 32 meters deep. In addition, the façade design had to fit into the listed ensemble of the campus. The architectural firm Deubzer & König finally convinced the jury with its design of an institute building with a large entrance hall and an attached laboratory area with a courtyard.

Even before completion of the Institute building, the Kaufmann and Meyer departments took up their research. Until the move, experiments were carried out in temporary laboratories in Monbijoustraße, opposite the Berliner Museumsinsel.

Infections and Immunity: The Departments of the Institute

Stefan H. E. Kaufmann (director from 1993 to 2019) headed the Immunology Department, where he researched the interaction between tuberculosis pathogens and their human host. Tuberculosis was the deadliest infectious disease in the world at the time the Institute was founded. This fact has not changed much to this day; in 2022, only COVID-19 was more deadly. Kaufmann's research focused on developing an improved tuberculosis vaccine, which is now close to approval.

With his Molecular Biology Department, Thomas F. Meyer (director from 1994 to 2020) explored the interaction between pathogens and host cells. Research focused on the role of bacterial pathogens in carcinogenesis and the development of host-directed therapies.

Arturo Zychlinsky was appointed third director of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in 2001 and heads the Institute today. With his Department of Cellular Microbiology, he investigates the potential immune function of DNA and DNA-associated proteins. The main topic is a defense mechanism of white blood cells discovered by the research group, the so-called "Neutrophil Extracellular Traps".

The fourth director, Emmanuelle Charpentier (director from 2015 to 2018), co-developer of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene scissors, founded the Max Planck Research Unit for the Science of Pathogens in 2018. Her research unit operates in the same building as the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, but the institutes are administratively independent of each other.

Research groups over time

Over the course of the Institute's history, numerous smaller research groups have been established, including the group of Thomas Rudel (from 1997 to 2008), Mark Achtman (from 1998 to 2008), Jörg Vogel (from 2004 to 2010), Hedda Wardemann (from 2006 to 2015), Kai Matuschewski (from 2009 to 2015), and Anca Dorhoi (from 2015 to 2017), as well as a senior group led by Fritz Melchers (from 2003 to 2016). Internationally, there was also cooperation with the partner groups of Thumbi Ndung'u and Alex Sigal (both from 2012 to 2021) in South Africa.

The Research Group Vector Biology, founded in 2011 by Elena Levashina, was continued and is part of the Institute today. It explores the role of the mosquito immune system in the development of malaria parasites. Through laboratory and field studies, Levashina aims to decipher how the environment, mosquitos, parasites and humans interact in the spread of malaria.

A new concept for the Institute

With the retirement of Directors Kaufmann and Meyer in 2019 and 2020, the MPG General Administration worked with the Institute’s management to develop a new concept for the Institute. In the course of this, six research groups, a Lise-Meitner research group and a Max Planck Fellow were appointed between 2017 and 2023. The six research groups are limited to five years with the option of renewal—they are led by Igor Iatsenko, Felix M. Key, Olivia Majer, Marcus Taylor, Matthieu Domenech de Cellès and Mark Cronan. Silvia Portugal is Lise Meitner group leader, and her research group is also temporary, but with an option for tenure. Most recently, Simone Reber was appointed to the Institute as a Max Planck Fellow for five years. Information on the research groups can be found on this website under "Research". The groups' research fields cover broad areas from microbiology, immunology, molecular biology to epidemiology—their diverse perspectives on infection biology shape the Institute today.