Thomas F. Meyer - Molecular Biology

The Role of Bacterial Infections in Human Carcinogenesis

The human mucosa is the major crossing point for molecular interaction between our body and the environment. This is where most pathogens initiate their infections and where our defense system is challenged to rapidly counteract any approaching assaults. Repeated or persistent onslaughts of this kind, however, tend to cause permanent damage to our epithelium, and, not surprisingly, the mucosal epithelium is the site most prone to carcinogenesis, a consequence of enhanced mutagenesis, inflammation and cell proliferation. Several clear links have been noted between chronic bacterial infections and carcinogenesis; however, the underlying mechanisms of this relationship are still sparsely understood.

Moreover, chronic colonization of the human mucosal surfaces by pathogens or changes in the composition of our microbiota may provoke harmful signals, misleading our immune and neuronal systems. In the long run, one of the consequences may be neuroinflammation. Exploring these mechanisms promises to pave the way towards better prevention and treatment of devastating diseases.

Our research applies sophisticated approaches to illuminate the relationship between infection and remote diseases, including cancer or neurodegeneration:

Carcinogenic microbes

The gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is the paradigm of a cancer-inducing bacterium. Understanding the mechanisms behind this link will help define the principles of an infection-cancer connection. We are also investigating the mechanisms behind the suggested carcinogenic effects of several other bacterial species, including Chlamydia trachomatis, Colibactin producing Escherichia coli.

Origin of cancer-initiating cells

While our understanding of cancer evolution and progression has greatly improved in recent years, the initiation of carcinogenesis is a much more elusive phenomenon. We are developing sophisticated genetic lineage-tracing tools to help illuminate the very earliest events in cancer initiation as a result of infection and the various stages of carcinogenesis.

Signatures of infection in the cancer genome

Unlike oncogenic viruses, bacteria do not leave genetic material in the genome of host cells. It is therefore much more difficult to prove that some bacterial infections can promote the emergence of cancer – often many years later. Nonetheless, epidemiology suggests that these bacteria-cancer relationships exist. Identifying genetic signatures that bacterial pathogens might leave behind in human cells might therefore provide genuine proof of the causality between infections and cancer emergence and facilitate our understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible. We are using the most advanced tools of molecular biology, genetics and genomics in order to identify such signatures.

Human organoids and mucosoids and other sophisticated research tools

The use of human primary cell culture models is crucial for authentic investigations of cancer emergence. We have pioneered the use of innovative organoid and mucosoid models, providing invaluable tools for modeling infection processes and their consequences in normal healthy cells.

Breakthrough technologies, such as RNA interference and CRISPR/Cas9, are extensively used in our work to decipher beneficial and potentially deleterious gene functions and genetic defects.

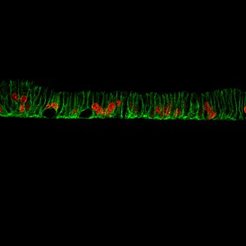

The unexpected link between our guts and the brain

Increasing evidence suggests an important link between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. Studies have revealed direct contact of the mucosal epithelium with nerve cells that directly lead to the brain. Specifically, the Nervus Vagus, part of the parasympathetic nerve system, transmits signals directly from the brain to the gut mucosa and the other way around, from the guts and the stomach to the brain. The information delivered appears to be manifold and includes inflammatory stimuli that may drive neuroinflammation and thereby the development of related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Numerous observations support this link; however, the mechanisms behind it are enigmatic and, thus, are the subject of our studies. The aim is to acquire a basic understanding and elucidate effective treatment and prevention options.